The Georgian government’s ‘shift’ toward Russia is largely based on pragmatism – Georgia is firmly in Russia’s sphere of influence and cannot escape this geographic reality. While the political elite is connected to Russia, the population is largely pro-Western and the EU is pushing Georgia to ‘pick a side’, forcing the state into a difficult balancing act. Conflict over Abkhazia and South Ossetia seems unlikely for now but the question of EU candidacy threatens the government’s leadership and could lead to unrest.

Georgia at a crossroads as the West encourages it to ‘pick a side’. Georgia is at a turning point. On one hand lies Russia, an indispensable trading partner, tied to Georgia historically and culturally, but considered an occupier by many and an existential threat to the country’s sovereignty. On the other is Europe – the Georgian people seek greater integration, but the EU makes promises it cannot keep and fatigue is rising. Georgia itself is of key geopolitical importance: its coast faces the Black Sea, offering the West a counterweight to Russian influence, and lies on both the East-West and North-South land trade routes. The country’s frozen conflicts, cultural dissonance, and deep ethnic division make it a potential flashpoint in an already unstable region. Much will depend on how the EU attempts to influence Georgia’s domestic politics and whether the government is able to successfully balance foreign relations and appeal to a somewhat contradictory public opinion.

Government shifting away from the West to a more pragmatic foreign policy. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, Georgia has offered a workaround for many sanctioned Russians and become a hub for parallel imports, largely thanks to the connections of the ruling elite. In recent years, the incumbent Georgian Dream party has faced protest for its pro-Russian stance and apparent slide toward authoritarianism. The arrest and imprisonment of former President Saakashvili was seen as an attack on political opposition, as has the recent attempt to impeach the pro-Western President, while a law on ‘foreign agents’ could have increased state control of the media. The reality however is that Georgia is and likely always will be in Russia’s geopolitical orbit. This ‘shift’ away from the West may be the result of a more pragmatic approach by the state – a vehemently anti-Russian policy could incite Russian aggression, while the EU has proven to be an unreliable partner.

EU’s priority is to counter Russian sanction avoidance through Georgia. Public sentiment is somewhat contradictory. Polls show that Georgians favour greater integration with the Euro-Atlantic but want to maintain good relations with Russia and do not necessarily support direct membership in the EU or NATO. Indeed, Georgia is still majority religious conservative and many would oppose the adoption of certain Western values especially as they relate to minority rights. To use a cliché, Georgia wants to have its cake and eat it, i.e., reap the benefits of good relations with Europe without committing to full ‘westernisation’. Last year, the EU made Georgia’s candidacy to the bloc contingent on twelve priorities for reform. At best, only three of these points have been fulfilled. While the priorities encourage pro-Western reform, some are clearly targeted at reducing Russian influence and blocking sanctions avoidance – we think this is the EU’s priority. The EU will decide on Georgia’s candidacy before the end of the year. It has two options: grant the candidacy hoping to encourage pro-Western sentiment and deny the government any vindication of its policies, or, more likely, reject the candidacy hoping for a change in government either through an immediate revolution or in the polls next year.

Parallels with Ukraine are limited – conflict unlikely for now. A casual observer may draw parallels between Ukraine and Georgia, especially considering the misrepresentation of the 2008 August war in the media. The war saw Russia support two breakaway regions and was presented as an act of unilateral aggression by Russia, who occupied Georgian land. In fact, the origins of the conflicts around Abkhazia and South Ossetia go back decades if not centuries and there are strong arguments in favour of their independence. Parallels with Ukraine are baseless – Georgia would not be able to defend itself against a Russian offensive given its size, and the West would find it challenging to come to Georgia’s aid given its isolation. Moreover, Russia has no desire for a conflict – Russia does not support independence or integration for Abkhazia or South Ossetia and instead seeks to maintain the status quo, as the contested territories prevent Georgia from joining NATO. The conflict is entirely frozen, the territories are largely autonomous and they contain no significant ethnic Russian populations. The situation could change if Georgia Dream loses power but we think this is relatively unlikely for now. The next key test for Georgia will be how the population reacts to the EU’s decision on candidacy.

Mastering the art of ambiguity – Georgia’s relationships

Too small to have true independence, Georgia must balance the opposing forces that seek to control the Caucasus. Georgia may not be able to fully comply with the EU’s anti-Russia stance – Russia is an indispensable trade partner with close historical and cultural ties, while the West is removed geographically and the potential for integration is limited. Thus, pressure from the EU to ‘pick a side’ may force Georgia toward Russia.

Based on polling, the Georgian population generally wants greater Europeanisation and closer ties to the Euro-Atlantic, but at the same time more closely aligns with Russia with its religion and conservative values. To use a cliché, Georgia wants to have its cake and eat it – it embraces the benefits that Westernisation brings but rejects some of the cultural changes that it implies, most notably regarding minority rights. This is also to say that while Georgia is both Western and Eastern, it is also neither – not quite Christian European and not quite Russian. It is simply Georgian, but unable to have true independence due its small population. Thus, Georgia will always be beholden to the West or Russia (or the Islamic world perhaps). As such, the Georgian leadership must remain ambiguous, toeing a careful line to appease both the West and Russia without alienating either or its own population. Thus, Georgia’s relationship with Russia is driven by pragmatism. Georgia is undoubtedly in Russia’s sphere of influence and Russia is both an existential threat to Georgia and an indispensable trading partner.

Russia’s strategy in Georgia since independence has been to counter Western encroachment. A Georgia that is a member of the EU or NATO is a Georgia that could base the US military and is, thus, quite rightly, a concern for Russia. Georgia has renewed importance since the start of the war in Ukraine as a way to bypass sanctions and as a trade route for parallel imports, a process that is facilitated by the close connections between the oligarchs of the two countries. Georgia also lies on an important trade crossroads – North-South for Russia, and East-West for Europe. The West has largely left Georgia alone and not actively sought deep integration for fear of antagonising Russia. In contrast to Ukraine, which is more traditionally ‘European’, Georgia is too far away and isolated for NATO to defend and signs of an upcoming commitment would likely lead Russia to act militarily. Indeed, the 2008 August war was a clear message to ‘Stay Back!’ The EU is more likely to use indirect means to influence domestic politics, including pushing for reforms and a change in government using the bait of EU membership. In the event of a conflict, we doubt the West would intervene beyond sanctions.

Georgia is geopolitically important as a crossroads for East-West and North-South trade through the Caucasus, as well as its placement on the Black Sea. Control of Abkhazia limits Georgia’s power on the Black Sea, while South Ossetia is within striking distance of major highways and pipelines and the capital of Tbilisi. Source: Stratfor

Ivanishvili and the Georgian Dream

Georgia is also strongly tied to Russia through its political elite, most notably Bidzina Ivanishvili, the country’s richest man and founder of the incumbent Georgian Dream party.

The Georgian desire to both Westernise and maintain positive relations with Russia may be mutually exclusive. At least on appearances, the West is categorical when it comes to Russia, accepting nothing other than a vehement opposition to Russia. This may be impossible for Georgia. Besides its cultural and religious connections, as well as the existential threat Russia poses, Georgia will remain firmly tied to Russia due to the connections of the political elite.

The most important of these connections is that of Bidzina Ivanishvili. Georgia’s richest man and éminence grise, Ivanishvili amassed a fortune during Russia’s free-for-all privatisation in the 1990s and was estimated in 2019 to be worth one-third of the country’s GDP. Ivanishvili founded the incumbent Georgian Dream party in 2011 and held two terms as Prime Minister in 2012 and Party Chair in 2018-21.

Ivanishvili is not openly pro-Russian. Indeed, his tenure as Prime Minister continued the pro-Western reforms passed under Saakashvili’s leadership. During Ivanishvili’s first term, Georgia continued to pursue integration with the Euro-Atlantic. However, his tenure as Party Chairman was a time of crisis for the country with protests leading to changes to the country’s electoral system. For the last several years, many have considered Georgian Dream to be sliding back toward Russia.

Despite retiring fully from politics, Ivanishvili still exercises considerable control over those in power with personal ties to many state officials, including in government and the judicial system. He has been accused of vote buying and his blessing on government polices remains essential, presenting problems for international investment in the country. Ivanishvili claims to have severed his ties to Russia in 2011 when he announced his intention to run for office. However, Ivanishvili is part of the group of oligarchs that came to power in the 1990s. It would be simplistic to say that such oligarchs owe loyalties to President Putin or each other, but there remains among the group a culture of soviet-era ‘blat’, an exchange of favours. As such, the allegations that Ivanishvili maintains deep connections with Russian oligarchs are believable, including for example helping Russians avoid sanctions, most notably Victor Yevtushenkov, majority owner of the conglomerate Sistema.

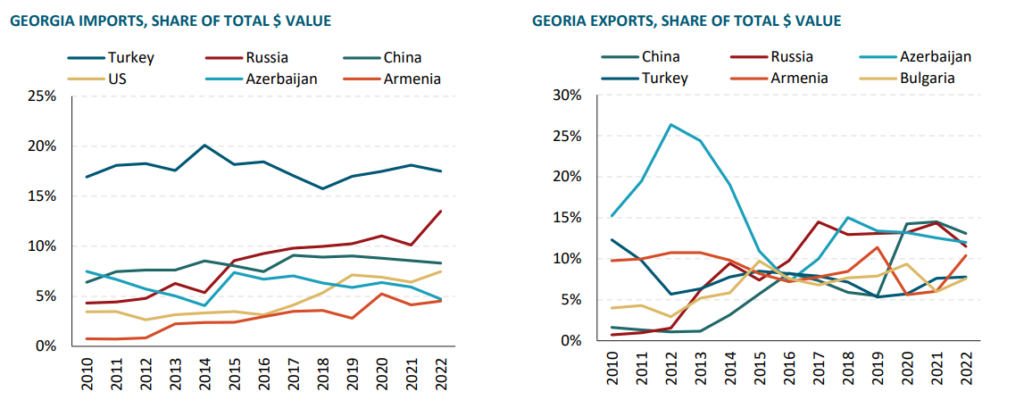

Exports are more diversified than imports, which are dominated by Turkey. In absolute terms, exports rose dramatically to the FSU in 2022, including to Russia, although Russia’s share in total exports declined. Source: World Bank, Trading Economics

The West’s POV: ‘De-oligarchisation’ but no commitment on integration

Georgia is making slow progress on the reforms needed to become an EU candidate. However, we doubt that either side actually considers membership a possibility. For now, the EU is using the bait of membership to undermine Russian influence in the country and manipulate domestic politics. We think the EU will again deny Georgia’s candidacy, hoping this will encourage a change in government.

Last year, the EU rejected Georgia’s application for ‘candidate’ status but will review its decision before the end of this year. The EU made Georgia’s candidacy subject to a list of twelve priorities, including judicial reform, efforts to combat corruption and improve media transparency, as well as more vague policies, including ‘de-oilgarchisation’. As of June, only three of the twelve priorities had been fully implemented.

We believe that ‘de-oligarchisation’ refers implicitly to Ivanishvili. The EU has called Ivanishvili ‘destructive’ and have called on the Georgian government to sanction him. Given the timing of the twelve priorities (during the war in Ukraine), we believe de-oligarchisation is more specifically targeted at stopping sanctions avoidance through Georgia rather than necessarily increasing the process of Europeanisation.

Apart from helping Russia avoid sanctions, the West is primarily concerned with what it considers to be Georgia’s drift toward Russian authoritarianism. Georgian Dream encountered fierce opposition when it tried to introduce a law on ‘foreign agents’ that would have granted the government greater control the press. Many have noted the similarities to the foreign agent law in Russia, but few have noted the parallels with the West’s clamp down on independent media. In any case, the government appeared to listen to the people and cancelled the law. There have also been criticisms of the party’s treatment of political opposition. Former President Saakashvili was arrested and imprisoned while the courts recently attempted to impeach the pro-Western President – both have widely been considered to have been politically motivated without particular reason (examining whether this is true or not is outside the scope of this report).

We think that the Georgian Dream’s ‘drift’ toward Russia has been made more out of pragmatism and fatigue with an unending string of promises by the West, rather than because of the preferences of the ruling elite. Ivanishvili naturally pays a role, but we think, even without his influence, Georgia would have to maintain a balanced foreign policy to maintain peace. Moreover, rather than ‘Putinism’, we think Georgian society may be more heavily influenced by plain old religious conservatism.

We note, however, that Georgian Dream is publicly committed to Europeanisation. In October, Prime Minister Garibashvili said the government had done its best to implement the recommendations and said the country expected the EU to make the “correct” decision, noting Georgia’s role in ensuring regional security. This rhetoric almost appears to us as a threat – Georgia is offering the EU one last chance to move toward integration before more decisively committing to Russia.

The EU’s twelve priorities are an attempt to goad Georgia away from Russia, and, while candidacy status is may be granted this year, it would largely be symbolic and membership will remain a pipe dream. As we see it, the EU has two options:

- Given the discretionary nature of some of the twelve priorities, the EU may conclude enough progress has been made and grant candidacy status with the option of withdrawing in the future, most importantly contingent on free and fair elections next year. The EU will be afraid that not granting Georgia EU candidacy will embolden Georgian Dream’s move toward Russia, as the party would use a refusal to vindicate their ‘balanced’ policy to the population. The EU will also base its decision on public opinion and polls shows high EU support. The EU will seek to maintain this popularity, relying on pro-EU sentiment as a driving force in internal politics.

- The EU does not recommend candidate status. The EU may want to send a message that the current government is failing the people, hoping to cause unrest in Georgia and encourage a change in power.

In either case, Georgia remains trapped by the geopolitical reality that it cannot leave Russia’s orbit. We think the Georgian government will still attempt to balance its foreign relations, i.e., maintain a positive relationship with Russia, despite the EU’s disapproval. On the other hand, however illusory the prospect of EU membership, abandoning a pro-Western policy would lead to a rise in public discontent. We see a high likelihood of protests against Georgian Dream if the EU does not grant candidacy and this will likely be reflected in next year’s election.

Russia’s POV: Abkhazia and South Ossetia and the potential for further conflict

Russia does not support Abkhazian independence or South Ossetian integration: it seeks to maintain the status quo, as this removes the threat of NATO encroachment. However, the current situation only deepens ethnic division and a clash may become inevitable. We doubt we will see this in the short-term as Russia and the West would be unwilling to engage, but domestic unrest and a change in government would increase the chance of a conflict.

Abkhazia and South Ossetia are two break-away regions that most countries recognise as a part of Georgia. Only a handful of countries recognise their independence, including Russia. The two regions have become synonymous with Russian occupation since the five-day august war in 2008. Since then, they have been considered a geopolitical flash-point, with many expecting renewed violence and, more recently, speculations of a second front in Russia’s war with the West.

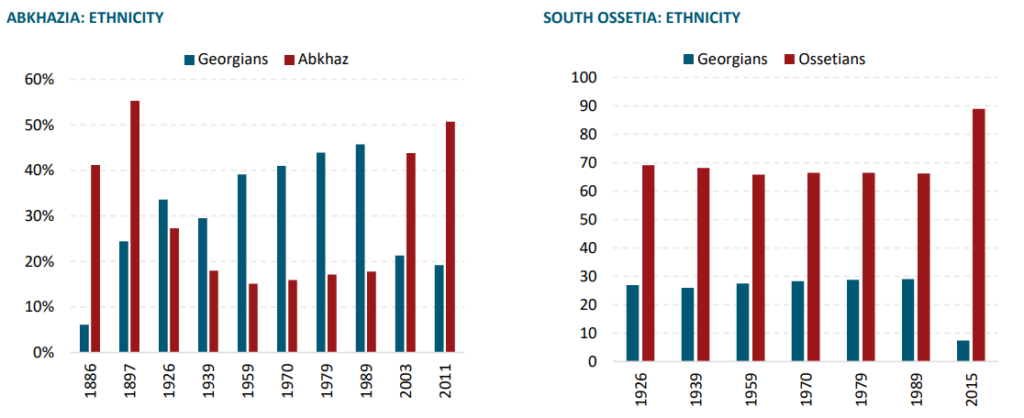

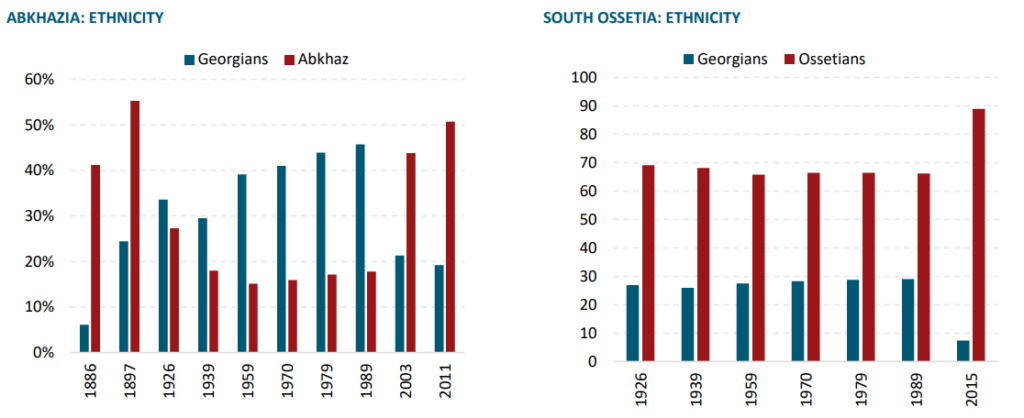

As always, the situation is far more complex than the official narrative. There is a precedent for local autonomy in both regions, not only since the collapse of the USSR, but going back generations, i.e., these conflicts did not emerge out of the ground. One need only look at the demographics of the regions to see that the 2008 war was not simply a Russian occupation of Georgian land and that there is popular support for Russia in the break-away regions.

The West’s POV: ‘De-Oligarchisation’ but no commitment on integration

Georgia is making slow progress on the reforms needed to become an EU candidate. However, we doubt that either side actually considers membership a possibility. For now, the EU is using the bait of membership to undermine Russian influence in the country and manipulate domestic politics. We think the EU will again deny Georgia’s candidacy, hoping this will encourage a change in government.

Last year, the EU rejected Georgia’s application for ‘candidate’ status but will review its decision before the end of this year. The EU made Georgia’s candidacy subject to a list of twelve priorities, including judicial reform, efforts to combat corruption and improve media transparency, as well as more vague policies, including ‘de-oilgarchisation’. As of June, only three of the twelve priorities had been fully implemented.

We believe that ‘de-oligarchisation’ refers implicitly to Ivanishvili. The EU has called Ivanishvili ‘destructive’ and have called on the Georgian government to sanction him. Given the timing of the twelve priorities (during the war in Ukraine), we believe de-oligarchisation is more specifically targeted at stopping sanctions avoidance through Georgia rather than necessarily increasing the process of Europeanisation.

Apart from helping Russia avoid sanctions, the West is primarily concerned with what it considers to be Georgia’s drift toward Russian authoritarianism. Georgian Dream encountered fierce opposition when it tried to introduce a law on ‘foreign agents’ that would have granted the government greater control the press. Many have noted the similarities to the foreign agent law in Russia, but few have noted the parallels with the West’s clamp down on independent media. In any case, the government appeared to listen to the people and cancelled the law. There have also been criticisms of the party’s treatment of political opposition. Former President Saakashvili was arrested and imprisoned while the courts recently attempted to impeach the pro-Western President – both have widely been considered to have been politically motivated without particular reason (examining whether this is true or not is outside the scope of this report).

We think that the Georgian Dream’s ‘drift’ toward Russia has been made more out of pragmatism and fatigue with an unending string of promises by the West, rather than because of the preferences of the ruling elite. Ivanishvili naturally pays a role, but we think, even without his influence, Georgia would have to maintain a balanced foreign policy to maintain peace. Moreover, rather than ‘Putinism’, we think Georgian society may be more heavily influenced by plain old religious conservatism.

We note, however, that Georgian Dream is publicly committed to Europeanisation. In October, Prime Minister Garibashvili said the government had done its best to implement the recommendations and said the country expected the EU to make the “correct” decision, noting Georgia’s role in ensuring regional security. This rhetoric almost appears to us as a threat – Georgia is offering the EU one last chance to move toward integration before more decisively committing to Russia.

The EU’s twelve priorities are an attempt to goad Georgia away from Russia, and, while candidacy status is may be granted this year, it would largely be symbolic and membership will remain a pipe dream. As we see it, the EU has two options:

- Given the discretionary nature of some of the twelve priorities, the EU may conclude enough progress has been made and grant candidacy status with the option of withdrawing in the future, most importantly contingent on free and fair elections next year. The EU will be afraid that not granting Georgia EU candidacy will embolden Georgian Dream’s move toward Russia, as the party would use a refusal to vindicate their ‘balanced’ policy to the population. The EU will also base its decision on public opinion and polls shows high EU support. The EU will seek to maintain this popularity, relying on pro-EU sentiment as a driving force in internal politics.

- The EU does not recommend candidate status. The EU may want to send a message that the current government is failing the people, hoping to cause unrest in Georgia and encourage a change in power.

In either case, Georgia remains trapped by the geopolitical reality that it cannot leave Russia’s orbit. We think the Georgian government will still attempt to balance its foreign relations, i.e., maintain a positive relationship with Russia, despite the EU’s disapproval. On the other hand, however illusory the prospect of EU membership, abandoning a pro-Western policy would lead to a rise in public discontent. We see a high likelihood of protests against Georgian Dream if the EU does not grant candidacy and this will likely be reflected in next year’s election.

Russia’s POV: Abkhazia and South Ossetia and the potential for further conflict

Russia does not support Abkhazian independence or South Ossetian integration: it seeks to maintain the status quo, as this removes the threat of NATO encroachment. However, the current situation only deepens ethnic division and a clash may become inevitable. We doubt we will see this in the short-term as Russia and the West would be unwilling to engage, but domestic unrest and a change in government would increase the chance of a conflict.

Abkhazia and South Ossetia are two break-away regions that most countries recognise as a part of Georgia. Only a handful of countries recognise their independence, including Russia. The two regions have become synonymous with Russian occupation since the five-day august war in 2008. Since then, they have been considered a geopolitical flash-point, with many expecting renewed violence and, more recently, speculations of a second front in Russia’s war with the West.

As always, the situation is far more complex than the official narrative. There is a precedent for local autonomy in both regions, not only since the collapse of the USSR, but going back generations, i.e., these conflicts did not emerge out of the ground. One need only look at the demographics of the regions to see that the 2008 war was not simply a Russian occupation of Georgian land and that there is popular support for Russia in the break-away regions.

A quick history lesson:

Following the Russo-Circassian war, the Russian empire launched a process of Russification in some of its Muslim populated regions in the south, including the deportation of up to 40% of the ethic Abkhazians from Abkhazia, after which the Abkhazians were left as the minority in the region. After independence was declared in the early 1990s, ethnic Georgians left the region or were forcibly expelled.

Ossetians migrated to the area of South Ossetia in the 17th century and have since become a majority. They did not have autonomy but were largely integrated into Georgian society. Though majority Ossetian, South Ossetia had never been a separate entity before the USSR. Many believe the creation of South Ossetia to be a form of Soviet colonialism.

No matter the historical basis, ethnic tensions were enflamed by Georgia’s first President, a staunch nationalist who ran on a policy of Georgia for the Georgians.

Ultimately, however, the importance of these regions for Russia lies in their political importance – they prevent Georgia from inclusion in NATO. This also explains the paradox in Russia’s strategy in Georgia. Russia at once feeds and tends to the problems in the South Caucasus. Nowhere else has Russia’s strategy most keenly been expressed in the Kremlin’s refusal to support a South Ossetian referendum to unite with Russia. Indeed, Russia does not support unification. It does not even support full independence. Russia must maintain the status quo. This does not exclude cooperation however, especially in terms of partnerships in the military and infrastructure.

Unlike Donbass, there is not a sizable Russian population in Abkhazia and South Ossetia and, even in the event of war, we doubt we will see a similar referendum in Russia on integration. That said, Russia’s policy encourages nationalist thinking in the regions, which is particularly difficult to manage in South Ossetia as it seeks to unite with North Ossetia, a part of Russia (Abkhazia for example has more autonomous aspirations). That is to say that conflict may become inevitable, albeit the form is hard to predict.

We doubt the West’s willingness to engage militarily in the region. Georgia would be very difficult to defend in case of any Russian offensive. Georgia is small and Tbilisi is within striking distance of Russia’s current position in South Ossetia. Moreover, violence in the country would a) immediately disrupt the only remaining land trade route from China to Europe, and b) potentially destabilise this route in the long-term. We think this risk is a consideration in the West’s policy in Armenia, i.e., the West needs an alternative East-West land route.

However, rather than providing justifications for the conflict, we wish to examine the facts as they stand. What we can say is that Russian support is not driven by benevolence. We believe Russian policy in the region is a pre-emptive measure to prevent Western encroachment in what Russia considers its near abroad. For example, as with Georgia proper, Abkhazia derives geopolitical importance from its Black Sea coast. Control of this region for Russia is not in and of itself a goal, but important because of an undesirable alternative – increased Western influence on the Black Sea. There is no significant advantage in controlling the area, but not controlling the area would put Russia at a disadvantage. South Ossetia meanwhile derives its geopolitical importance from its location in the Georgian heartland, located within striking distance of major gas pipelines, highways and the Georgian capital.

Ultimately, however, the importance of these regions for Russia lies in their political importance – they prevent Georgia from inclusion in NATO. This also explains the paradox in Russia’s strategy in Georgia. Russia at once feeds and tends to the problems in the South Caucasus. Nowhere else has Russia’s strategy most keenly been expressed in the Kremlin’s refusal to support a South Ossetian referendum to unite with Russia. Indeed, Russia does not support unification. It does not even support full independence. Russia must maintain the status quo. This does not exclude cooperation however, especially in terms of partnerships in the military and infrastructure.

Unlike Donbass, there is not a sizable Russian population in Abkhazia and South Ossetia and, even in the event of war, we doubt we will see a similar referendum in Russia on integration. That said, Russia’s policy encourages nationalist thinking in the regions, which is particularly difficult to manage in South Ossetia as it seeks to unite with North Ossetia, a part of Russia (Abkhazia for example has more autonomous aspirations). That is to say that conflict may become inevitable, albeit the form is hard to predict.

We doubt the West’s willingness to engage militarily in the region. Georgia would be very difficult to defend in case of any Russian offensive. Georgia is small and Tbilisi is within striking distance of Russia’s current position in South Ossetia. Moreover, violence in the country would a) immediately disrupt the only remaining land trade route from China to Europe, and b) potentially destabilise this route in the long-term. We think this risk is a consideration in the West’s policy in Armenia, i.e., the West needs an alternative East-West land route.