In this first of two reports on the state of play in Kazakhstan, we examine the country’s domestic politics. Much-needed reforms have been slow since the January 2022 protests. With the appointment of a new pro-reform PM, however, the wheels may finally be in motion. The appointment is a good sign that Tokayev is sincere about his reform plans, but much still rests in the president’s hands, as his power remains absolute.

Kazakhstan – Central Asia’s post-Soviet success story. Kazakhstan is one of the most attractive countries for long-term investment and business growth in the former Soviet Union. Located in the heartland of Eurasia, Kazakhstan boasts a massive natural resource base, maintains territorial integrity and has a strong foreign policy. As a petrostate, Kazakhstan has successfully invested its oil wealth into a solid and diverse economy, developing into a middle-income country that attracts foreign migrants. However, Kazakhstan continues to battle the problems that led to the 2022 protests. Levels of corruption and wealth inequality are high, the economy remains reliant on raw material prices, and the ruling regime maintains a tight grip over information and cyberspace. Still, there are signs of progress. Last year, the economy grew by 5% with foreign investment totalling $13.3bn in the first half alone. Kazakhstan is benefitting from the indirect effects of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, including the influx of professional migrants, and the relocation of those companies and funds forced to leave the Russian market, as well as those Russian companies forced to change jurisdiction.

Bloody January and the shift in power. Former President Nazarbayev oversaw Kazakhstan’s strong economic growth for almost three decades. However, the country has been no stranger to protest thanks to wealth inequality, corruption and inefficient governance. The corruption became offensively obvious during the COVID pandemic, forcing Nazarbayev to step down from the presidency, although he retained control behind the scenes. Discontent continued, however, coming to a head in January 2022 when violence erupted nationwide. In response, President Tokayev, in office since 2019, promised extensive reform and began to ‘clear out’ the old guard from positions of authority. The evidence points to a coup attempt during the events of Bloody January, but by who one can only speculate. The result was clear though – the balance of power shifted dramatically in favour of Tokayev.

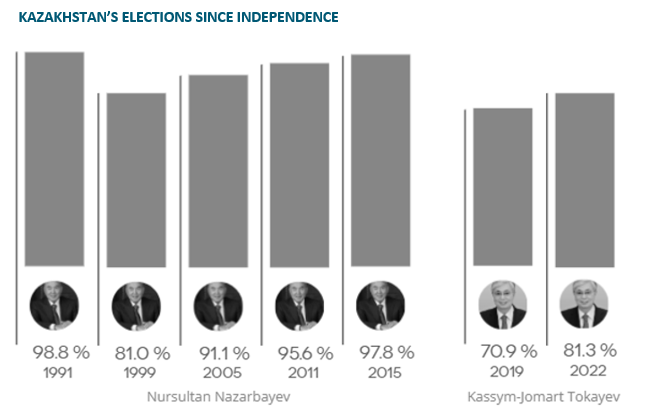

Reforms have been slow – an illusion of democratisation. Tokayev accurately assessed that stabilisation was impossible without responding to the demand for comprehensive reforms. He announced the need for constitutional reforms and a transition from a “super-presidential form of government to a presidential republic with a strong Parliament”. However, a closer look at the constitutional changes reveals that the president’s power remained absolute. After the referendum, Tokayev held snap elections – an apparent exercise in democracy. However, rather than addressing discontent, these elections were a way to get ahead of any strong opposition and provide sufficient time for Tokayev to enact his promised reforms. Kazakhstan’s is a phantom democracy and fair elections and greater political accountability will likely remain elusive for decades.

New cabinet bodes well. Tokayev was apparently discontent with the status quo, last Monday dismissing the government that has been in power since 2022, following a lack of meaningful reform, the failure of the state to sufficiently curb inflation, and the recent earthquake in Almaty that highlighted the failings of the Ministry of Emergency. On February 6, Tokayev appointed Olzhas Bektenov as the new Prime Minister. Bektenov is definitely a man of the new generation, born only 11 years before the collapse of the Soviet Union, he is a relative unknown. While Former PM Smaiylov was a transitory figure, unlikely to offend the old guard, Bektenov is clearly anti-Nazarbayev and pro-reform. As head of the Anti-Corruption Agency, Bektenov helped dismantle the old guard’s power after 2019. The appointment is a choice that signals Tokayev remains focused on a modern, long-term development strategy. While the majority of the cabinet has retained their jobs, Bektenov’s arrival may suggest that Tokayev is finally ready to launch full economic and political reforms under his own specifications. Still, the prime minister remains fully accountable to the president and the extent and success of Bektenov’s work will depend on Tokayev’s sincerity in his calls for change. We think this is a solid argument in favour of Tokayev. However, time will tell.

New Kazakhstan or more of the same

Kazakhstan is Central Asia’s post-Soviet success story and the posterchild for digital-authoritarianism. As a petrostate, Kazakhstan has successfully invested its oil wealth into a solid and diverse economy, developing into a middle-income country that attracts foreign migrants and is not dependant on remittances from Russia unlike its neighbours. However, levels of corruption and wealth inequality are high (though better than average for the region), the economy remains reliant on raw material prices, and the ruling regime maintains a tight grip over information and cyberspace.

While Kazakhstan is no stranger to protest, the violence that gripped the country in January 2022 was unprecedented. While the state has presented the riots as terrorism, there has been no significant investigations into the events, and the evidence suggests a behind-the-scenes shift in power. Who exactly led the coup is unclear but President Tokayev clearly came out on top.

Tokayev was quick to announce constitutional reforms to address the discontent, but the amendments lacked political substance. Rather than shift to a more decentralised power structure, Tokayev consolidated authority and retained almost all the power of his predecessor, Nazarbayev. Tokayev then held snap-elections – rather than an exercise in democracy, this was a bid to gain public support, and get ahead of any potential challenges to his authority.

Since then, reform has been slow, leading many, including myself, to question Tokayev’s sincerity and whether indeed his leadership is much different to Nazarbayev’s. However, the recent appointment of the young reformer Olzhas Bektenov as Prime Minister is a good sign that Tokayev may be finally ready to push forward reforms under his own specifications.

The causes of Bloody January

Despite strong economic growth, wealth inequality, corruption and inefficient governance led to frequent protests in Kazakhstan. Exacerbated by the COVID crisis and the lack of meaningful change, these protests turned violent in January 2022.

After the collapse of the USSR, the story in Kazakhstan played out much as it had in the rest of the former-Soviet republics, with leadership and wealth consolidated among those with links to the former Soviet government thanks to rapid and unregulated privatisation and land ownership. Since independence, Kazakhstan’s political and bureaucratic system has been dominated by these Soviet-era oligarchs, most notably Nursultan Nazarbayev. Having established himself for decades within the Soviet system, Nazarbayev served as President from 1990 until 2019, making him one of the longest-ruling, non-royal leaders in the world. Although overseeing a period of strong economic growth, Nazarbayev was an autocratic leader and cultivated a pervasive cult of personality.

Source: RFERL

Kazakhstan was one of the best performing economies in Central Asia thanks in large part to its natural resources, high oil prices, and market-oriented reforms. Foreign investments also fuelled the country’s modernisation – Nazarbayev was a strong diplomat, maintaining good relations with foreign powers and integrating Kazakhstan into regional organisations, while sharing the spoils of oil and gas extraction. However, corruption and wealth inequalities remain high, with 162 Kazakhs holding 55% of the nation’s wealth as of 2022 (WSJ). Since independence, the government has co-opted or suppressed those critical of its policies resulting in a lack of democratic opposition.

The late 2010s saw protests over human rights abuses in 2018 and following the deaths of five children in a house fire in Astana in 2019, a case that exemplified Kazakhstan’s wealth inequality and the government’s apathy, and exposed the public’s lack of confidence in state structures. The outrage led Nazarbayev to dismiss the government and then, unexpectedly, to announce his own resignation as President. Nazarbayev was replaced by Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, then the speaker of the upper house of parliament, but kept his position on the Security council “for life”. This was Nazarbayev’s retirement. Already 80, he was likely setting the stage for a relative to take over. By all accounts, Tokayev was seen as a neutral, transitory figure that would toe the line until a suitable candidate from Nazarbayev’s clan was found. Nursultan Nazarbayev still continued to rule behind the scenes through his position in the security services.

The COVID period made Kazakhstan’s endemic corruption offensively obvious. The legacy effects of the pandemic on the economy meant high inflation and rising energy prices, ironically hitting the country’s oil-producing regions the hardest. Discontent was on the rise thanks to austerity measures, a lack of economic government stimulus, and the ongoing influence of Nazarbayev. Protests erupted in January 2022 after the state decided to drop subsidies on LPG, causing the price of the fuel to double overnight. The unrest quickly spread to Kazakhstan’s main urban centres and quickly and surprisingly turned violent.

Peaceful protests began in the western oil-producing regions, with the protestors making reasonable demands and open to dialogue. Protestors insisted that the government had repeatedly ignored the declining living standards and called for economic, social, and political reform with greater checks and balances on centralised power.

However, within days, the protests spread to the urban centres, especially in the former capital of Almaty, where riots began and police began to fire on protestors. This unexpected development caused many to speculate that the protests were co-opted by forces hostile to the government including from within Nazarbayev’s own clan. Most likely, we think, is a domestic coup attempt. Given Kazakhstan’s ‘dual’ leadership in 2019-22, officially led by Tokayev, but nominally ruled by Nazabeyev, this coup could have come from either direction – either a coup against Tokayev by Nazerbayev, or a coup against Nazerbeyev by Tokayev.

Whudunit and how power shifted in the state

Rival clans most likely co-opted the protests in an attempt to change the power structure within the country. Before 2022, President Tokayev had been making tentative steps against the old guard, who may have fomented violence and staged a coup to remove him. On the other hand, Tokayev himself may have been behind the coup – the protests were the perfect opportunity to strike hard against the Nazarbayev clan. In either case, the outcome was a clear win for Tokayev.

Winston Churchill once compared Kremlin political struggles to bulldogs fighting under a carpet: “an outsider only hears the growling, and when he sees the bones fly out from beneath, it is obvious who won.” The same can be said for any post-Soviet state. Thus, any analysis of the attempted coup is a speculative exercise.

After Tokayev became president in 2019, it soon became apparent that he would not live up to the expectations set for him. Tokayev had a reputation within elite circles as a neutral and unambitious technocrat, well-suited to handling a transition of power without rocking the boat. However, in the run up to 2022, Tokayev was becoming increasingly independent.

How can we say that Tokayev was both neutral and an ally of Nazarbayev? One often hears about the leading ‘clan’ in Kazakhstan, e.g., the Nazarbayev clan that controlled most of the power structures until 2022. The clan system in Kazakhstan should be understood as dynamic and made up of often overlapping political groupings rather than familial relations (though they also fall along such lines). That is to say, when we speak of the Nazarbayev clan, we are not referring only to the Nazarbayev family.

This clan structure is also not the only set of political groupings within the country, with clans running alongside a system of parallel states – namely the formal civilian bureaucracy, the security service and the corporate sector. While Tokayev had been seen as a political ally of Nazarbayev, he was at the same time neutral within the clan structure. Nazarbayev lost his position within the state in 2019, but his clan, either directly or indirectly, retained significant control of the country, most significantly through the security service and the corporate sector.

Even prior to 2022, Tokayev was making steps to curtail the power of the Nazarbayev clan, testing the waters for his own rules and possibilities. In 2021, Tokayev paused construction on the highly-corrupt Astana Light Rail Transit, which had seen millions of dollars siphoned off to those with ties to the Nazarbayev clan. Once Tokayev had ‘cleaned house’ after the January protests, the project was restarted as part of Tokayev’s vision to turn Kazakhstan into an economic power. Prior to 2022, Tokayev also led the authorities to open an investigation into Nazarbayev’s nephew for tax evasion.

Following the protests, Tokayev acted swiftly to further cut out the Nazarbayev clan. Nazarbayev’s direct relatives were dismissed or gave up assets, including the dismissal of the senior administration of Samruk-Kazyna, the state’s National Welfare Fund, who had strong ties to Timur Julibayev, one of Nazarbayev’s son-in-laws, who was himself dismissed as President of Kazakhstan’s main entrepreneurs’ organisation, the Atameken Union. Two of Nazarbayev’s other son-in-laws were dismissed from companies belonging to the Samruk-Kazyna group. Nazarbayev’s nephew was dismissed from his position as second in command of the KNB (the country’s security service), his eldest daughter relinquished her seat as a senator, and his youngest daughter gave up her company. Another nephew, Kairait Satybaldy, who was suspected of instigating the January events, was sentenced to six years in prison for embezzlement, while investigations were launched into suspicions of extortion by Nazarbayev’s brother (these investigations were carried out by the Anti-Corruption agency under the leadership of Olzhas Bektenov, the newly-appointed Prime Minister as of writing).

In 2022, many senior officials, including half of the deputies in office, and staff within the security forces were dismissed. However, no systematic work has been carried out to evaluate the security forces’ response to the protests or bring the real perpetrators to justice. The trail of Karim Masimov, an alleged beneficiary of the unrest, was held behind closed doors, preventing him from disclosing information that would implicate other actors. If the protests had grass-roots origins, one could assume that justice would have been more clearly served.

The result was not a purge – many of those dismissed were replaced by their deputies or at least those who had spent their career in the appropriate branch of administration, i.e., those that had not previously been within Tokayev’s circle but now perhaps owed the president their promotion. Undoubtedly, the Nazarbayev clan retain significant influence over a large share of the economy – the shift in power was insufficient to completely remove the old guard, but sufficient enough to threaten any that wished to challenge Tokayev’s new-found authority. The lack of deep investigation and oversight of the cause of the protest also avoided raising too much opposition.

So Tokayev was challenging the Nazarbayev clan prior to the protests and then launched a strong reorganisation of power in the months that followed. Thanks to the shutdown of the internet during the riots, and the lack of transparency or investigations following the events, real evidence of provocateurs is lacking. There are some reports that suggest the security forces were complicit in the rioting, including the police standing down in areas and allowing looting and rioting to proceed unimpeded.

The most likely explanation is that the Nazarbayev clan co-opted the protests through the security forces in an attempt to oust Tokayev after he became a threat to their authority. With the help of the Russian-led CSTO and having taken serious measures to prevent the riots, Tokayev prevented the coup and then proceeded to dismantle Nazarbayev’s remaining influence.

However, Tokayev’s decisiveness could suggest prior organisation – the lightning speed call and reaction of the CSTO, the reversal of the cancelled fuel subsidy, the rapid move to remove Nazarbayev and take over as Head of the Security Council, the swift justice against the so-called perpetrators but without significant investigation, the call to fire on rioters, and the prompt creation of a narrative fit for public consumption could all support the theory that the coup was orchestrated by Tokayev himself.

In either case, the result was the same – a clear win for Tokayev.

Referendum and constitutional amendments: Phantom Democracy

A closer look at the constitutional amendments made in 2022 show simply the illusion of change: the president retains all his former powers. The snap elections that followed were again a repeat of a familiar pattern – Nazarbayev often held snap elections after controversies to prevent meaningful opposition. The result is a shift in dynasty rather than a move toward greater democratisation.

Tokayev accurately assessed that stabilisation was impossible without responding to the demand for comprehensive reforms. He announced the need for constitutional reforms and a transition from a “super-presidential form of government to a presidential republic with a strong Parliament”, presenting the amendments as a change in state mentality with the old Soviet-era system representing a drag on the country. The reforms were meant to ‘depersonalise’ the presidency, including a maximum term of a single 7-year period, clearly differentiate the president as a person and the president as an institution, and shift the balance of power to strengthen the parliament and the legal system.

However, a closer look at the constitutional changes reveals that Tokayev retained most of his previous powers and indeed had consolidated his power through the removal of Nazarbayev’s influence in the security forces. Rather than reform, the outcome was a mere change in dynasty hidden behind populist rhetoric – key issues remained untouched, including the legacy of the Soviet economy, which is hostile to the free creation of new industries, and the lack of trust between the state and society, exacerbated by the mass shootings and police abuses of January 2022.

In May 2022, only several months after the protests – not enough time to allow meaningful and inclusive discussion – the law on constitutional amendments was published. The law proposed more than 50 amendments and the public was given one month before the referendum was to be held.

A pattern emerges when one examines the amendments – ultimately, changes were made on a superficial level while still allowing the president ultimate control. For example, the government is accountable to the parliament and the president, but the president decides on the formation of the government and can dismiss it on his own initiative. Parliament can pass a vote of no confidence in the government, but it is up to the president to accept or reject the resignation. Moreover, the president retains the right to dismiss parliament outright.

Another example: despite demand to abolish the Senate entirely, the amendments simply reduced the number of senators directly appointed by the president from 15 to 10, while granting the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan (APK) the right to appoint 5 senators. However, the APK is an advisory body under the president, thus Tokayev keeps his 15 senators. The rest of the senate are elected by local councils (which are overwhelmingly members of the presidential party) and the president has the right to dissolve any local council. That is to say that Tokayev maintains the right to exclude any senator should he choose so.

Source: Civicus Lens

After the referendum, Tokayev held snap elections – an apparent exercise in democracy. However, rather than addressing discontent, calling a snap election was a repeat of a pattern extending back to independence. Nazarbayev held snap elections as a way to avoid any real, well-prepared challenges to his own re-election, usually following some scandal in the opposition or a failed piece of legislation.

Originally planned for 2024, Tokayev held snap elections in 2022. Cynically, these elections were a way to remove uncertainty among Nazarbayev loyalists and prevent them from regrouping in time to challenge the 2024 elections, to get ahead of any potential criticism arising from the economic and political fallout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and provide sufficient time for Tokayev to enact his promised reforms.

Again repeating the pattern stretching back to the USSR, Tokayev won in 2022 with 81.3% of the vote, with the nearest challenger (also from a pro-government party) trailing with only 3.4%. Kazakhstan’s is a phantom democracy and, while we see hope for economic reforms, fair elections and greater political accountability will likely remain elusive for decades.

State of play in 2024 and the dismissal of the cabinet

Kazakhstan’s economy has proved strong despite headwinds but this is not because of some great leadership or policy. However, the recent appointment of a new pro-reform, anti-Nazarbayev Prime Minister suggests Tokayev may be sincere in his desire for change and that the lack of meaningful reform thus far has been due to a necessary focus on short-term stability. Time will tell.

Last year, the Kazakhstani economy grew by 5% with foreign investment totalling $13.3bn in the first half alone. This strong economic performance does not come in spite of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, but in part because of it. Kazakhstan is exposed to vulnerabilities in the Russian economy, for example the tenge lost 20% against the dollar in the first several weeks of the conflict. When Russia suspended certain exports to the EAEU, Kazakhstan felt an immediate impact on the price and availability of some basic foodstuff. Russia also suspended the pipelines that transit Kazakhstani oil exports four times in 2022 (c80% of oil exports transit through the Russian pipeline system). However, Kazakhstani exports to Russia actually increased by 22% in the first ten months of 2022, while Kazakhstan is benefitting from the indirect effects of the conflict, including the relocation of those companies and investment funds forced to leave the Russian market, as well as those Russian companies forced to redomicile abroad. Kazakhstan may also be benefitting from the influx of middle-income, educated Russian men that left Russia to avoid the draft, many of whom work in highly demanded professions, such as IT, also supporting Kazakhstan’s transition to a digital economy.

Although not without risk, Kazakhstan remains one of the most attractive countries for long-term investment and business growth in the former Soviet Union, given a massive natural resource base, territorial integrity (Georgia and Azerbaijan are both involved in ongoing foreign conflicts), a strong foreign policy, including success in avoiding sanctions while maintaining ties with Russia, and as an ‘alternative’ to Russia in the developing markets for Western business.

However, Kazakhstan continues to battle the economic problems that led to the 2022 protests, and it is becoming increasingly clear that reforms are slow. The January protests highlighted that there is widespread discontent among the population and such protests are likely to repeat should Tokayev continue to drag his heels on meaningful reform. Indeed, much of Kazakhstan’s success since 2022 has arguably come from external factors, rather than domestic policies.

Moreover, the protests set a powerful precedent. The crackdown in 2022 had surpassed the levels the state had previously gone to repress dissent. The state shut off wired and mobile internet across most of the country for six days, and telephones went down in Almaty and several other regions. This example of techno-autocracy is fundamentally opposed to the idea of the ‘digital Kazakhstan’ that Tokayev is trying to sell his foreign partners. Kazakhstan has gone to considerable lengths to promote the idea of a digital economy and has had relative success in branding itself as a welcoming and attractive environment for tech and innovation. However, the shutdown led to massive losses for tech companies. Even if it is not repeated, the shutdown created a precedent that may give digital nomads, IT exiles, and crypto miners cause to hesitate when considering Kazakhstan as a destination. Kazakhstan can ill-afford to spook the foreign nationals if it hopes to successfully diversify its economy.

The constitutional amendments and the snap elections in 2022 represented a change in dynasty rather than a shift toward democratisation, suggesting that Kazakhstan will remain autocratic for the foreseeable future. Nazarbayev still has five years left in his term and it is hard to say thus far whether he will overstay his self-imposed term limits. Doing so would be bold. We would sooner bet on Tokayev retaining powerful positions, perhaps within the security forces, and allowing a new pro-government president.

However, there is reason to be hopeful about the course of other reforms. One explanation for the lack of meaningful reform since 2022 is the need to prioritise short-term goals. The referendum and snap elections in 2022 were window dressing to appease protestors, while the government was focused on maintaining stability. The Russia-Ukraine conflict began only a month after the January protests and has undoubtedly had consequences in Kazakhstan – addressing these changes and preventing instability as a result should and likely was the main short-term priority for Tokayev, e.g., avoiding sanctions by association, handling the influx of migrants, and balancing the changing international power structures and the economic fallout.

The recent cabinet reshuffle may suggest that Tokayev has decided to finally implement change.

Tokayev was apparently discontent with the status quo, last Monday dismissing the government that has been in power since 2022. Why was the cabinet dismissed now? It’s unclear, but we can speculate. The recent earthquake in Almaty highlighted the failings of the Ministry of Emergency, the government has been criticised for failing to sufficiently bring down inflation and attract further investments (despite FDI coming in at $26-28bn for 2023), and the Ministry of Finance failed to introduce a new tax code. There have also been several disappointments in major industries during the current government’s tenure. Several cities were left without heat in 2022 due to the critical condition of some 15 thermal power plants, requiring billions of tenge to repair. Several major incidents involving dozens of deaths, occurred in Arcelor Mittal’s mines, which some say could have been prevented if the government had introduced effective safety measures. We also note that Kazatomprom, Kazakhstan’s behemoth in uranium mining, announced it would likely see a dip in production in 2024 due to infrastructural delays and problems procuring sulfuric acid, a key component in uranium extraction. Coincidentally (or not) Tokayev met with the senior management of Kazatomprom shortly before dismissing the government.

The government was appointed during the transition phase after the 2022 crisis, and Prime Minister Alikhan Smaiylov may have been seen as a safe option at the time, a temporary figure. With Tokayev aiming to double GDP by 2029, he may have been looking for a more ambitious and aggressive replacement, someone with a broader outlook beyond the near-term crisis objectives – someone not from the Nazarbayev era, and someone who can push the country away from Soviet-era mentalities.

On February 6, Tokayev appointed Olzhas Bektenov as the new Prime Minister. Bektenov is definitely a man of the new generation – born only 11 years before the collapse of the Soviet Union, he is a relative unknown. He has worked over the years in a range of positions, including in the office of the prime minister and as head of the presidential administration.

While Smaiylov was a transitory figure, unlikely to offend the old guard, Bektenov is clearly anti-Nazarbayev and pro-reform. As head of the Anti-Corruption Agency, Bektenov criticised the body’s earlier work and began investigations into the business dealings of those close to Nazarbayev.

The appointment is a choice that signals Tokayev remains focused on a modern, long-term development strategy. While the majority of the cabinet has retained their jobs, Bektenov’s arrival may suggest that Tokayev is finally ready to launch full economic and political reforms under his own specifications. Still, the prime minister remains fully accountable to the president and the extent and success of Bektenov’s work will depend on Tokayev’s sincerity in his calls for change. We think this is a solid argument in favour of Tokayev. However, time will tell.